Some books I read my class this year

Reading to your class is awesome. There are lots of sound developmental and pedagogical reasons for doing it, and you can find out all about them at this excellent ‘Reading aloud’ page on the National Library of NZ Services to Schools website. The page provides professional reading, research and evidence, examples of good practice, and strategies for making things happen in your classroom. It’s helpful, inspiring, thorough, and I encourage all teachers to take a look.

Now, because this page exists I do not have to cover reading aloud in any kind of general way and can concentrate on my own teaching experiences and approaches; my role-model, how I do it, books I’ve read this year, and thoughts relating to the first and second of these. It's a bit patchy but let's begin.

Some teachers don't do it? Really?

During a break from teaching I worked at the National Library, and at first I was surprised the ‘Reading Aloud’ page existed. It never occurred to me that there might be a need; that some teachers didn’t like reading to their class and/or didn’t see it as important and/or lacked confidence. Discovering this stuff was a legit “what? Really?” moment.

Check out my dad

It’s my dad’s fault I was surprised. His name was Geoff Neville1 and he was a primary school teacher and principal. Because growing up we lived in very small towns with very small schools, I was usually in his class. And he read to us every day. It was an integral part of my schooling and I didn't realise it wasn't the same for everyone until I was an adult.

My father was amazing at reading aloud. His ex-students remember just how amazing:

It’s hard to explain exactly why my father was so good at it. He was excellent at voices and timing and phrasing, and he was passionate, but there was also some kind of x-factorish magic. He could read to any kids, any age, any time and they’d be spell-bound. The text choices were ballsy; All three volumes of Lord of the Rings to a bunch of small-town New Zealand eleven year-olds?! And this was in the 80s, before the movies or any kind of mainstream hype. Back then it was just some Oxford don deep fantasy nerd niche shit. But he totally pulled it off and for the six months it took to get through the story we were enraptured.2

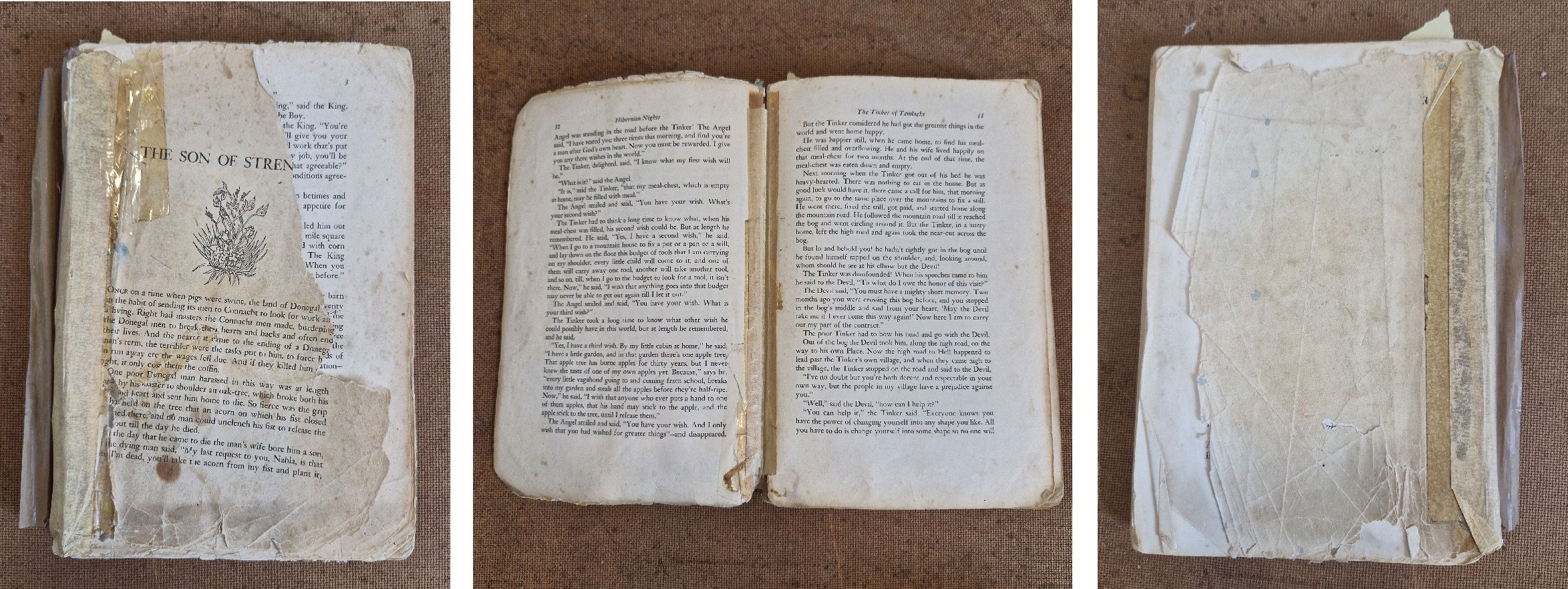

(As an aside, one of dad’s favourite read-alouds was Hibernian Nights, a 1963 collection of traditional Irish fairy tales and myths by Seumas MacManus. It was not designed for kids but was rather a bunch of hardcore celtic stories filled with gaelic words, ancient lyrical pacing, scary magic, and acts of weird brutality. For any other teacher, a terrifying prospect. But my father read them to everyone and everyone loved them. I have his copy of the book. Look how beautiful it is, well-loved and used, gorgeously disintegrating and falling apart. A family taonga).

Family copy of Hiberian Nights by Seumus MacManus - front, middle and back

In my classroom

So I learnt about reading aloud from my father. He was my role-model and I’m lucky I got to experience him doing it both as his student and as a teaching colleague. I learnt it’s magic either way. I have never not done it.

As a teacher who reads I’m not a patch on Geoff Neville but I think I’m pretty decent (perhaps I have a genetic predisposition?) Here’s what I do:

- Different voices for different characters. Top tip! If you can, make the character who does the most speaking your own voice. It can be weirdly physically difficult to maintain silly accents over long periods of time.

- Read at least 15 minutes a day. It takes at least this long to get through a decent chunk of the story. If the kids are really into it (and I’m in the mood) I’ll read longer, sometimes a whole hour. Reading aloud totally counts as part of the government’s ‘required daily hours of literacy’. It is legitimate and defendable. (I dunno, perhaps your deputy principal is a National-voting dick and tries to take you on?)

- Do it around about the same time each day, in the early afternoon. But I’m not too precious. If on a particular day it fits somewhere better, I’ll go with it.

- Let the kids doodle or fiddle while listening, and sit how and where they want. This year I had a couple of students who sometimes wanted to read their own books instead of listening to me read mine. All good.

- Chat about personal connections to the book or give anecdotes. Like how my middle name is Charlotte because Charlotte’s Web was my mother’s favourite book. Or that my friend Matt Taite made Te Wehenga and it’s the first bilingual book to win the Margaret Mahy Book of the Year Award and yes, I know famous people. Or that spiritualism was a big bonkers thing in the beginning of the 19th century and it involved taking photos of ghosts or bits of ghosts, like Humphrey’s lingering ectoplasm elbow in The Great Ghost Rescue. Or that the ocean taniwha in Gavin Bishop’s book Taniwha are my favourite because I have a general love of sea monsters and I visited Loch Ness and went for a swim and it was freezing but totally worth it to have shared the same world as Nessie, even for just for a minute, but also taniwha are not the same as Scottish sea monsters and it’s important to understand and respect that.

- Not really talk about anything officially ‘educational’ like story structure or word types or author intentions. If something pops up relating to work we’re already doing, for example a really great pun when we’ve been exploring homynyms, I might point it out. But I won't go on about it. I want the class to experience read-alouds as stories rather than texts; as a time for immersion not analysis.

- Never read a new book beforehand. This is because I like to discover and feel things alongside the kids, and also because it’s kind of thrilling as a teacher to have to suddenly swerve mid-story if something dodgy comes up. I don’t think this approach is recommended, you’re meant to read the story beforehand and rifle out the inappropriate bits. But I just love a classroom think-on-your-feet challenge!

(It seems to mostly happen in relation to race. For example in Porangi Boy by Shilo Kinothe, the 'n' word appears. I had to come to a screeching halt and we had to have a discussion about its use, what character was saying it and why, and how I actually found it personally quite uncomfortable to speak out loud. And in Eva Ibbotson’s Which Witch? the term ‘black magic’ is used to describe evil and harmful spells and actions. I talked about how I found the term ‘black’ problematic in this context and as a class we decided to use the term ‘bad magic’ instead. I just replaced it throughout the text. Job done). - Read lots of different kinds of books. There’s variety in form, e.g. long and short, novels and picture books, different genres and authors, heavy messages and light entertainment, and variety in content, i.e. what the stories are about. I’m a fan of the Mirrors and Windows theory which basically says book selections should both reflect children’s experiences and open them up to new ones. (That link goes to a National Library Services to Schools explanation which is much fuller). But I’m not too rigid about it. Sometimes I read a story just because I think it’s cool.

(There are a couple of exceptions. I never read comics3 or poetry. Comics because they rely on the combination of image and text to make meaning and when comics are read out loud, the picture has to be verbally described which cancels out the visual aspect and defeats the purpose.4 I don’t do poetry because basically I don’t like it.5 Yes, I know! Throw up your literary hands in horror and no doubt you’re right but the truth is I find most poems just a bit yuck. I’m not proud of myself. (I only dislike reading poetry for pleasure. I'm happy to cover it in ‘formal’ lessons).6

Books I read in 2025

Here are some books I remember reading to my class this year:

The first and second books

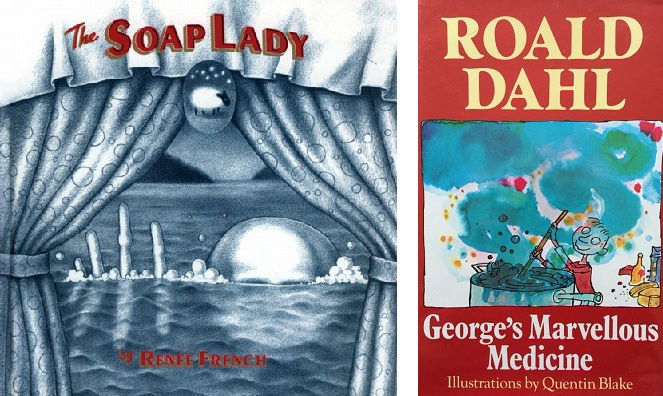

The Soap Lady by Renee French is the first story I read to a new class. It’s about “...a boy, a monster, a ventriloquist dummy, a number of bloodthirsty townspeople, and those soap horns your mom used to give you in the bubble bath”.7

I read it first for the following reasons:

- It's a great story.

- It’s a favourite of mine (you can’t fake enthusiasm. Another reason for not reading poetry).

- It’s a picture book. This sets up picture books as legitimate and valuable, even in a senior class (I’ve mostly taught year 7 and 8).

- The pictures are beautiful and unsettling.

- The students are unlikely to have heard it before.

- It’s weird. This helps set up our class as a place where eccentricity is welcome

- There is happiness and sadness. This shows that picture books can be serious and that stories can be many things at once.

- It’s by a woman. This is good role-modelling.

- It was inspired by a real saponified (turned to soap) female mummy that resides in a Philadelphia museum. This is a cool anecdote to tell after you’ve read the book (or before. I don’t suppose it matters).

George’s Marvellous Medicine by Roald Dahl is the second book I read. Here’s why:

- It’s a great story.

- It’s a favourite of mine (like I said, you can’t fake enthusiasm).

- My copy has the Quentin Blake illustrations which are beautiful and hilarious.

- It’s likely familiar to the kids, and if they don’t know this story then they’ll know another one by Roald Dahl. They get the vibe, it’s safe, and after the jolt of The Soap Lady, this is a nice thing.

- There are heaps of opportunities for funny voices.

- It’s short, taking about a week to read. This is long enough to establish a daily listening-to-a-spread-out story routine without being taxing.

- Most children can read it independently. Quite often after I read a story there are kids who want to do this.

The Soap Lady by Renee French and George's Marvellous Medicine by Roald Dahl

I want to end with an anecdote (and one of my 2025 favourite teaching moments). I was reading The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon and the class was silent. Some kids were mucking around with fidget toys, lots were drawing, I think one of them was doing embroidery. Then (spoiler alert) I got to the big reveal, where Christopher (the main character) finds out it was his father who murdered the neighbour's dog. There was a loud collective gasp of surprise and every single child lifted their head and looked straight at me in horror. The power of the story. It ruled.

Footnotes

1 My dad died in 2006. I miss him.

2 Obviously he skipped all the long boring dwarf and elf songs.

3 I purposefully say comics not graphic novels. Here’s why.

4 I have thoughts about the definitions and attributes of comics. You can read them here.

5 There are many reasons I don’t much like poetry. I need to write a whole other blog post.

6 There are these things called ‘verse novels’ which have the narrative structure of a novel but use poetry to tell the actual story. Apparently they can be very engaging and lots of kids and teachers love them. Personally, I can't think of anything worse but you definitely shouldn’t listen to me and instead you should visit the National Library's 'Verse Novels' page.

7 Description from here.

8 Description from here.