Te Tiriti o Waitangi: Aspirations, Rights and Interests 101 - part one

The term ‘aspirations, rights and interests’ is one you hear a lot in the discourse surrounding Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi). Until about a year ago I really had no idea what it meant and thinking this might be true for others in my demographic* I thought I’d try and provide a kind of Aspirations, Rights and Interests 101 (I’m going to use the acronym ARI from now on).

It’s a scary ask. I am pākeha and no way no how not ever an expert in Te Tiriti o Waitangi. I do however require some understanding in my public service job1 and have worked hard to achieve this (although ‘achieve’ is a misnomer. It’s a process of continuous learning and regular failure). I also aspire – professionally and personally – to be tangata Tiriti so am obligated always to share what I learn and to talk about racism (and when you discuss the Treaty you are always in some way talking about racism).2 And I’m open to being ‘wrong’, in fact it is more than likely in parts. Please give me feedback.

So I’m appropriately nervous but also hopeful that given my audience, a limited entry-level pākeha explanation (which is all this is) of ARI might be a positive thing. To grasp Te Tiriti o Waitangi, I myself have had to really really really break things down. Perhaps this is what others need too.

A last few contextual things – firstly this post is not a history of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. It doesn’t cover how and when it was signed, motivations for doing so, how it was abused by the Crown, the fight for recognition, efforts at redress etc. There’ll be a necessary bit of background, but my focus is ARI.3

Second, this essay has been reviewed by a Māori colleague. He said it’s appropriate for its intended audience and encouraged me to share it.

And finally, please take the following as read -

- Everything I say is problematic and contestable, including these bullets

- The Crown has not/does not do all that it should

- The Crown should be partnering with Māori in everything

A 1938 painting by Macus King of Tamati Waka Nene signing the Treaty in front of James Busby and Captain William Hobson. Image from National Library of NZ

The necessary bit of background

Te Tiriti o Waitangi is the name of the agreement made in 1840 between the British Crown (represented by William Hobson) and Aotearoa New Zealand (represented by about 540 rangatira). Essentially its purpose was to enable British settlers and tangata whenua to live together under a common set of laws.

There were versions of the Treaty in English and Te reo Māori. Both contained three Articles but the words used to articulate these weren’t the same in both languages. The two signatories’ understandings and expectations of Te Tiriti were therefore different.5

Here’s a very basic summary of each Article and the contested terms:

Article One provides the Crown with the right to govern the land. In the Māori version the word used is kawanatanga which pretty much does mean governance. But the English version gives the Crown sovereignty, a much stronger word and concept.

Article Two provides Māori with the right to make decisions over resources. In Te Reo this was termed te tino rangatiratanga or the unqualified chieftainship over lands, villages, property and treasures (taonga). In English, rangatira were given the much weaker exclusive and undisturbed possession.6

Article Three provides Māori with the Queen’s protection and the rights of British subjects (citizenship). It’s generally accepted the language means the same in both versions.

These differences in language are a massive deal. Simply put, the English version allowed things the Te reo version didn’t and over time the Crown took full advantage of this.7 It’s only now, after a century of protest and resistance that the Māori words and concepts of Te Tiriti are dominant,9 i.e. references to Article One are usually about kawanatanga/governance not sovereignty, and those to Article Two are about te tino rangatiratanga/chieftainship not possession. Article Three is and has always been about citizenship.

The Te Tiriti ki Waikato-Manukau or Waikato-Manukau Sheet is the only Treaty page to be written in English. It bears William Hobson’s seal and signature (which was very shaky owing to a recent stroke) and was signed by 39 rangatira, including and at least one woman. Image from Archives New Zealand

What does ARI mean in the context of Te Tiriti o Waitangi?

Let’s start with some basic definitions:

Aspiration: a strong desire or ambition to achieve something significant (hopes/aims)

Right: a just and inarguable claim to something (legitimacy/authority)

Interest: a share or stake in something (involvement/inclusion)

To adhere to Te Tiriti o Waitangi the Crown8 must consider the impacts on all three things in all significant policy decisions, as they relate to Māori. Consideration needs to include both positive and/or negative impacts.

The three Articles in the Treaty direct how this is to be done.

Remember how Article One of the Treaty gives the Crown the right to govern? To govern means to conduct the policy, actions, and affairs of a state (or some other kind of organization) with authority (in this instance the authority given by Te Tiriti and the Rangatira who signed it).

In Aotearoa, inherent in the word ‘govern’ is an obligation to consider the ARI of Māori. Good governance means doing this. Hands down. Full stop.

Article Two provides for te tino rangatiratanga, which gives Māori the right to control their own resources and taonga. ‘Resources’ generally refers to things like land and water. ‘Taonga’ approximates ‘treasure’ (but is actually much more) and includes items pākeha might consider intangible like tikanga, language and population data.

Article Two requires the Crown to particularly consider ARI in any decision or action that impacts resources or taonga (taonga-type interests).

In Article Three the Crown promises that the advantages of New Zealand citizenship are owed equally to Māori. This Article is about equity. It mandates specific consideration of ARI in decisions or actions that impact Māori differently from other population groups (equity-type interests).

Equity-type interests can represent a risk or opportunity. For example the Covid vaccine roll-out was a risk; the Three Waters co-governance arrangement is an opportunity (this is way simplistic but you get the point).

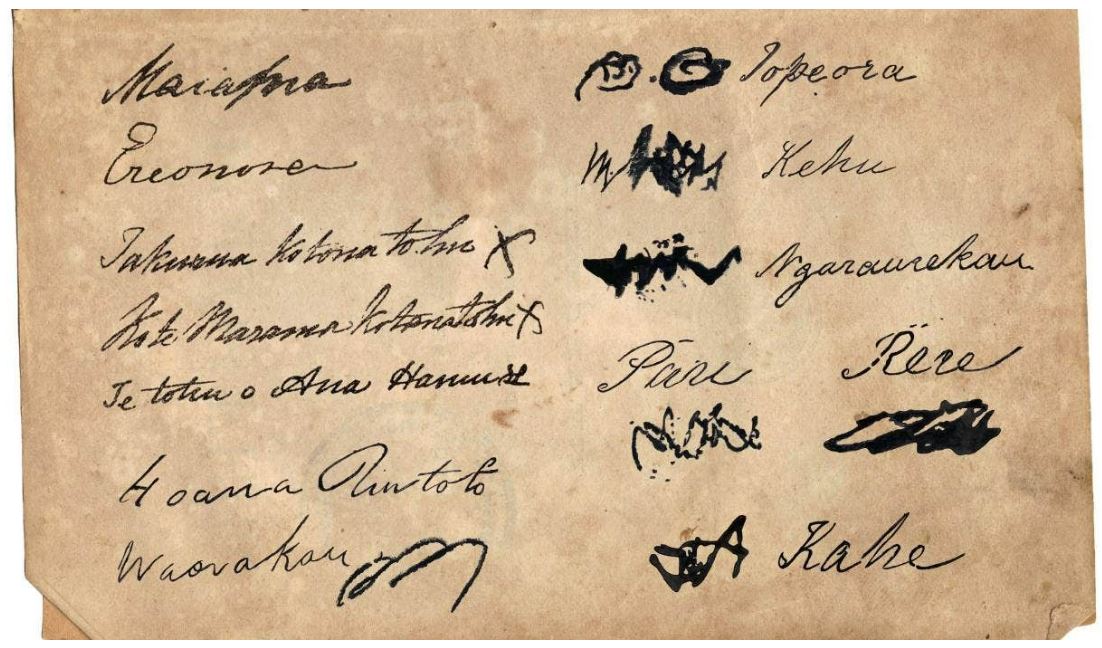

This image shows the signatures of two of thirteen women known to have signed the Treaty of Waitangi. Go here to find all their names and when and where they signed. Image from Te Ara Encyclopedia of NZ

I'm going to stop writing now. I will do another post on this topic (and I did) but it's complicated and important and I don't want to rush it.

Footnotes

* Pākeha, left-leaning, middle class, arty, politically aware, wanting to learn, and aspiring to be tangata Tiriti etc.

1. As do all public servants (aspirational at this point).

2. Even when talking about racism is difficult. In fact it should be because the subject is complex, important and brutal. Basically, if you do not find conversations about racism unsettling, then you are not having them right.

3. Lots of easily accessible versions of this information already exists e.g. at The Waitangi Tribunal, Archives NZ and NZ History.

5. You can find further detail about the differences between the two versions here.

6. Article Two also gave the Crown exclusive rights to purchase Māori land but the exact meaning of this is ambiguous. Some rangatira understood it to mean the Crown had first option, rather than a unique right to buy.

7. Possibly the greatest understatement ever in all of space and time.

8. In 2023 ‘the Crown’ pretty much means central and local government elected representatives and agencies ,and Crown entities.